Research

Our overarching goal is to understand the interaction between the genome and the environment. We have been taking advantage of the excellent infrastructure and generous funding available at OIST to explore how next-generation analytical tools can be used to answer a wide range of fundamental questions in ecology and evolution. As technological advances have equalized the playing field, decreasing disparity of analysis possible for model and non-model systems, we are particularly interested in working with unusual organisms, whose unique biology seems best suited to the questions at hand. Our major research projects are currently focused on understanding the (a) genetic mechanisms involved in social insect caste determination, (b) exploring the genetic consequences of co-evolutionary interactions between symbionts, (c) understanding the interplay between time, geography and genomics structure. We are also interested in developing new next-generation sequencing tools to facilitate our research.

Honey bee and parasite/pathogens evolution

Genetic basis of the “waggle” dance

Genetic basis of host switch by Varroa mites on the Western honeybee

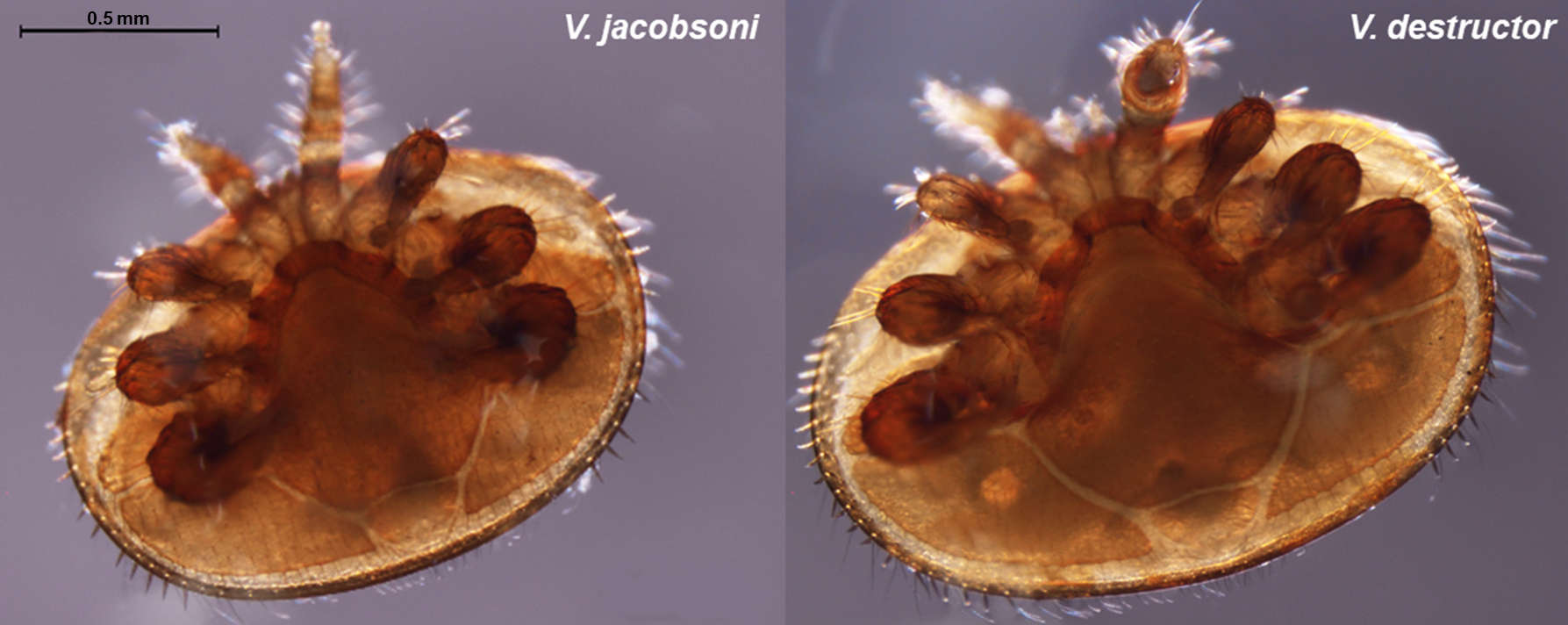

The domestication of the Western honey bee and globalization have facilitated the arrival and spread of new parasites and pathogens including the Varroa mites. Since Varroa destructor successfully switched host from the Asian honeybee (Apis cerana) to the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera) in multiple independent events, it has spread almost worldwide. Not only the ectoparasite induce direct damages via spoiling haemolymph but it is also a virus vector leading to its consideration as one of the main driver of honeybee global decline. Concerns rise as the sister species V. jacobsoni has emerged as an additional threat with the recent jump reported 10 years ago in Papua New Guinea.

The domestication of the Western honey bee and globalization have facilitated the arrival and spread of new parasites and pathogens including the Varroa mites. Since Varroa destructor successfully switched host from the Asian honeybee (Apis cerana) to the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera) in multiple independent events, it has spread almost worldwide. Not only the ectoparasite induce direct damages via spoiling haemolymph but it is also a virus vector leading to its consideration as one of the main driver of honeybee global decline. Concerns rise as the sister species V. jacobsoni has emerged as an additional threat with the recent jump reported 10 years ago in Papua New Guinea.

How did those specialized organisms repeatedly “jump” and adapt onto a new host? What are the potential genetic and population key factors enabling such events?

Our project aims to tackle some of these questions using next-generation sequencing technology and genetic analysis of mite populations from their original and new hosts. We sequenced and assembled de novo the genome of both V. destructor and V. jacobosoni mite in order to quantify the structure of the parasite genomes and to identify which genes have evolved due to recent selection. The comparison of whole genome of mites collected from their native range will allow to i) identify genetic mechanisms associated with the host switches by the mites, ii) detect historical signatures of selection after the host switch, iii) determine if gene flow has or still occured among populations and between mites species.

Collaborators: Maeva and Sasha

World biogeography and population genomics of an invasive mite

Since V. destructor has spread globally, it offers the opportunity to reconstruct a novel parasite spread and population evolution at large scale. For that we have started to build a world mite collection with the help of numerous collabotors to retrace the history of V. destructor populations using IM and ABC demographic models.

From where did the invasive Varroa came from? What could be the size of the source population(s)? Are the invasive populations genetically connected? So many questions that we hope to answered, to be continued… ![]()

![]()

Collaborators: Maeva and Sasha

The hidden power within - studying the honey bee microbiome

The fact that we, no matter where we are, are surrounded by for our eyes invisible tiny organisms - microorganisms - is fascinating. Microbial communities are small worlds for themselve, full of interactions. The great influence that microorganisms have on their environment is something we just started to understand.

The realization that we are not only surrounded by, but that in fact all multicellular organisms are closely associated with diverse microbial communities with profound effects on host life history traits – revolutionized our understanding of animal biology. There is a current need for a mechanistic understanding of interactions between members of microbial communities and their hosts, knowledge that will facilitate discovery of exciting new facts in animal biology. The knowledge to functionally understand and manipulate microbiomes could be usefully applied to diverse research areas such as health or agriculture. Yet, the complexity of microbiomes with interactions between members, and their consequences on hosts make most host-microbiota systems difficult to study. The experimentally tractable system of the honey bee offers an ideal opportunity to fundamentally explore functions and interactions of symbionts on host fitness, as the associated microbial communities are small, specialized, and individually cultivable.

Our goal is to get fundamental insights into host-microbiome relationships using the honey bee and its symbionts as model system. To do that we are using a combination of molecular methods and controlled experiments.

We are currently trying to tackle several project questions but mainly the two below:

1) Meta-transcriptomics, exploring genotype-derived microbiome differences over time

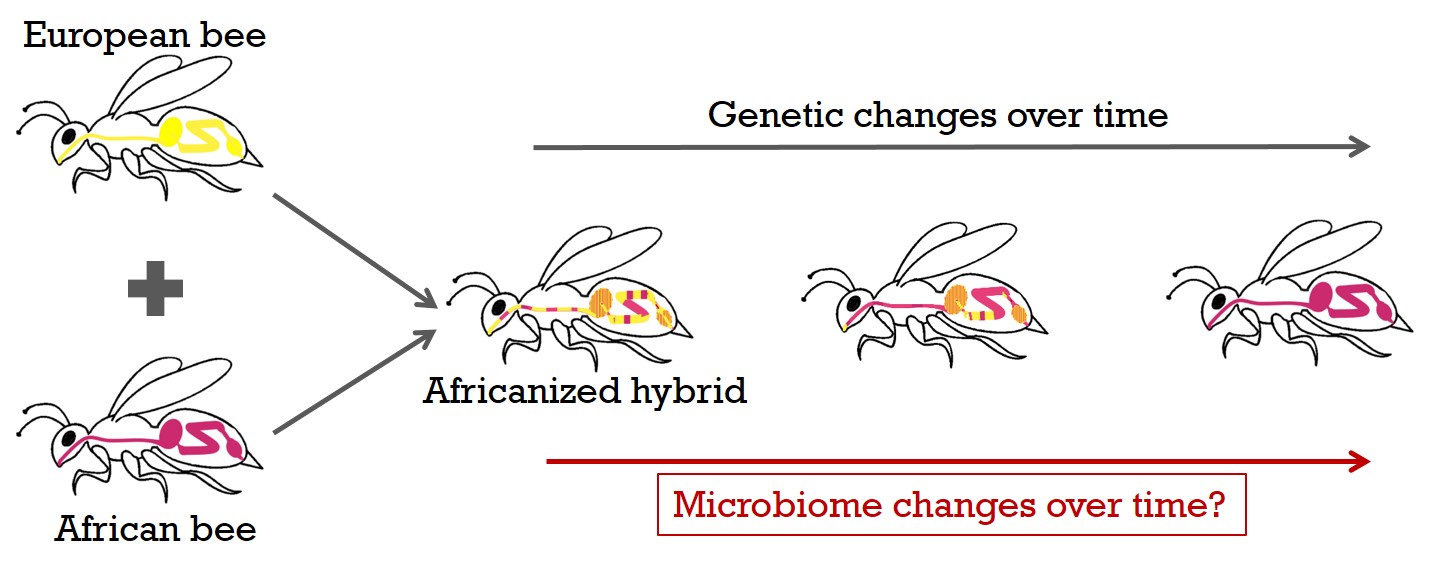

The microbiome can provide its host with flexibility beyond that encoded in host genomes, as rapid changes in microbial community composition or individual microbial genomes can directly affect important host life history traits. Therefore, the microbiome may enable rapid acclimation to new environments and resistance to environmental disturbances.

We can take advantage of a historical, unique data set consisting of many hundreds of honey bees sampled for more than a decade in the U.S. and Mexico, to generate a detailed picture of the internal microbiome, as well as of associated virus and host transcriptome responses by total RNA sequencing. During this time, a hybridization event from introduced African with wild US-European bee lines occurred. This invasion of the western hemisphere by the African honey bee genotype in less than 50 years and the subsequent spread of the Africanized hybrids is one of the most successful and rapid biological invasions known. Diverse genetic bee backgrounds in the same natural environment, will allow me to examine how host genetics affect microbiomes in the field.

2) Functional experimental tests on microbiota-mediated effects

Several studies could already demonstrate that the microbiome plays a crucial role in honey bee health and that a disturbed microbiota (e.g. due to antibiotic treatment) will result in sick bees. This is particularly important as honey bee health has been a major concern, following colony losses worldwide in the last decade. Still, we just started to realize the importance of the microbiome in this story and there are still many open questions that need to be answered. Raising honey bees under sterile conditions in the lab give us the option to do controlled experiments to disentangle the effects and interactions between microbial members, the host and stress factors. Research can be like a puzzle and if enough puzzle pieces have been found, they need to be put together to get a picture. If this can be managed in the promising honey bee system, it could lead to new ways of tackling current problems. For example by avoiding specific antibiotic treatments which are thought to protect the bees but are disturbing their microbiome, or by providing bee probiotics.

Collaborators: Vienna and Sasha

Venom evolution

Venom Components Project

Suites of genes underlie most phenotypes. Changes in these quantitative phenotypes can occur through changes in coding sequence, but more importantly occur through changes in gene expression. The relevance of gene expression change in phenotypic change has been established in a wide variety of organisms. However, what is still unclear is how changes in gene expression lead to evolution of a complex trait through deep time.

Snake venom is a combination of different proteins where the expression of each toxin can be traced and quantified to a specific genomic locus. The expression of each toxin alters its relative abundance in the venom inluencing the efficacy of the venom. Thus, we classify the toxin levels as the polygenic phentype that is snake venom. Drawing analogies from quantitative genetics, we model the effect of phylogeny on gene expression levels between different toxin genes in snake venom. This gives us a picture of how evolution has impacted relationships between toxin expression levels, which in turn effects how the snake venom phenotype is shaped. This project uses comparative transcriptomic data from 45 different snake species. We provide the first comprehensive look into snake venom evolution by combining quntitative, comparative, and phylogenetic concepts under a unified framework. This has allowed us to disucss a novel model snake venom evolution.

Stay tuned for updates about the manuscipt, which is presently under preparation.

Collaborators: Agneesh and Sasha

Gene Neofunctionalization Project

Essentially all the genes that constitute genetic makeup of any Eukaryote originally evolved for completely different role that they’re playing today. So if we want to uncover the history of life on Earth in its fullest, we should know what predisposes a gene to change function and how this change happens. The problem is, that most of those changes took place long time ago and it is almost impossible to reconstruct them. However there are several systems that evolved relatively recently or otherwise left enough evidence to trace their origin. That is the reason why we chose venom genes as our model to study gene neofunctionalization.

All venom genes evolved from a physiological gene via the change of expression pattern, structure and very often – copy number. And even though all venomous lineages of animals got their venoms independently, they all share a core profile of gene classes, like phospholipases or serine proteases. So while venom of a honey-bee has a dramatically different effect than that of a viper, they are very similar in terms of their components and evolutionary paths that led to their existence.

Currently we are using available genomes to figure out the evolution of snake venom genes. We are aiming to discover their non-toxic counterparts and trace duplication and mutation events that brought them here. We’re hoping that this project will shed light onto the evolution of genes in general for at some point in their evolutionary history all genes experienced a change of function.

Collaborators: Ivan and Sasha

Spider silk evolution

All spiders, across more than 45,000 species, produce some kind of silk. Silk is used for everything from sticking sand grains together to spinning dragline fibers or snaring prey by hand. It is assembled into trap doors, orb webs, and diving bells. A highly structured and hierarchical protein material, silk can take the form of sticky glues, nanofibrous mats, bundles of threads, or thin ribbons, and can exhibit a wide range of mechanical properties. How does evolution fine-tune and modify such a complex phenotype over time? We are combining (1) transcriptomics and proteomics research on spider silk with (2) cutting edge microCT analysis of silk gland morphology and (3) the physics of protein assembly to understand this remarkable relationship.

All spiders, across more than 45,000 species, produce some kind of silk. Silk is used for everything from sticking sand grains together to spinning dragline fibers or snaring prey by hand. It is assembled into trap doors, orb webs, and diving bells. A highly structured and hierarchical protein material, silk can take the form of sticky glues, nanofibrous mats, bundles of threads, or thin ribbons, and can exhibit a wide range of mechanical properties. How does evolution fine-tune and modify such a complex phenotype over time? We are combining (1) transcriptomics and proteomics research on spider silk with (2) cutting edge microCT analysis of silk gland morphology and (3) the physics of protein assembly to understand this remarkable relationship.

Collaborators: Rob and Sasha

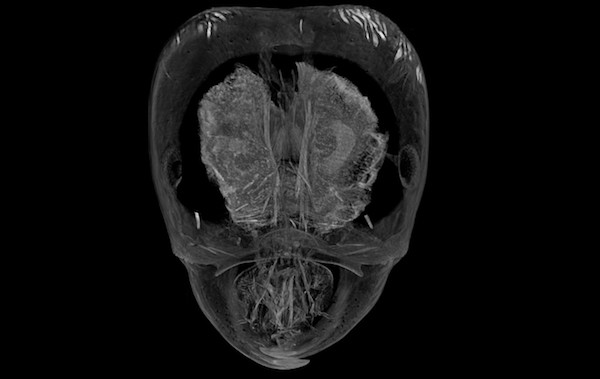

Visualizing parasitization with microCT

Phorid flies in the genus Pseudacteon are specialized parasitoids of Solenopsis fire ants. Female flies lay their eggs in the abdomens of fire ant workers. After hatching the larval parasitoid then travels to the head, where it feeds on mandibular muscle and changes the host ant’s behavior to keep itself safe. Little is known about the physical interactions between the parasitoid and its host. We are using microcomputed tomography (microCT) to visualize the development of larval phorid flies in situ.

Phorid flies in the genus Pseudacteon are specialized parasitoids of Solenopsis fire ants. Female flies lay their eggs in the abdomens of fire ant workers. After hatching the larval parasitoid then travels to the head, where it feeds on mandibular muscle and changes the host ant’s behavior to keep itself safe. Little is known about the physical interactions between the parasitoid and its host. We are using microcomputed tomography (microCT) to visualize the development of larval phorid flies in situ.